The U.S.-led team behind the research say the technology, known as in-vitro gametogenesis (IVG), could one day help people who are infertile to have biological children. However, they stressed it’s still at least a decade away from being available.

Dr. Paula Amato of Oregon Health & Science University, one of the study’s authors, explained that the technology could allow women who no longer produce eggs — as well as same-sex couples — to have children genetically related to them.

The breakthrough, published in Nature Communications, comes after years of progress in reproductive science. For example, Japanese researchers recently created mice with two biological fathers. But this new study marks a milestone by using human DNA rather than animal models.

Here’s how it worked:

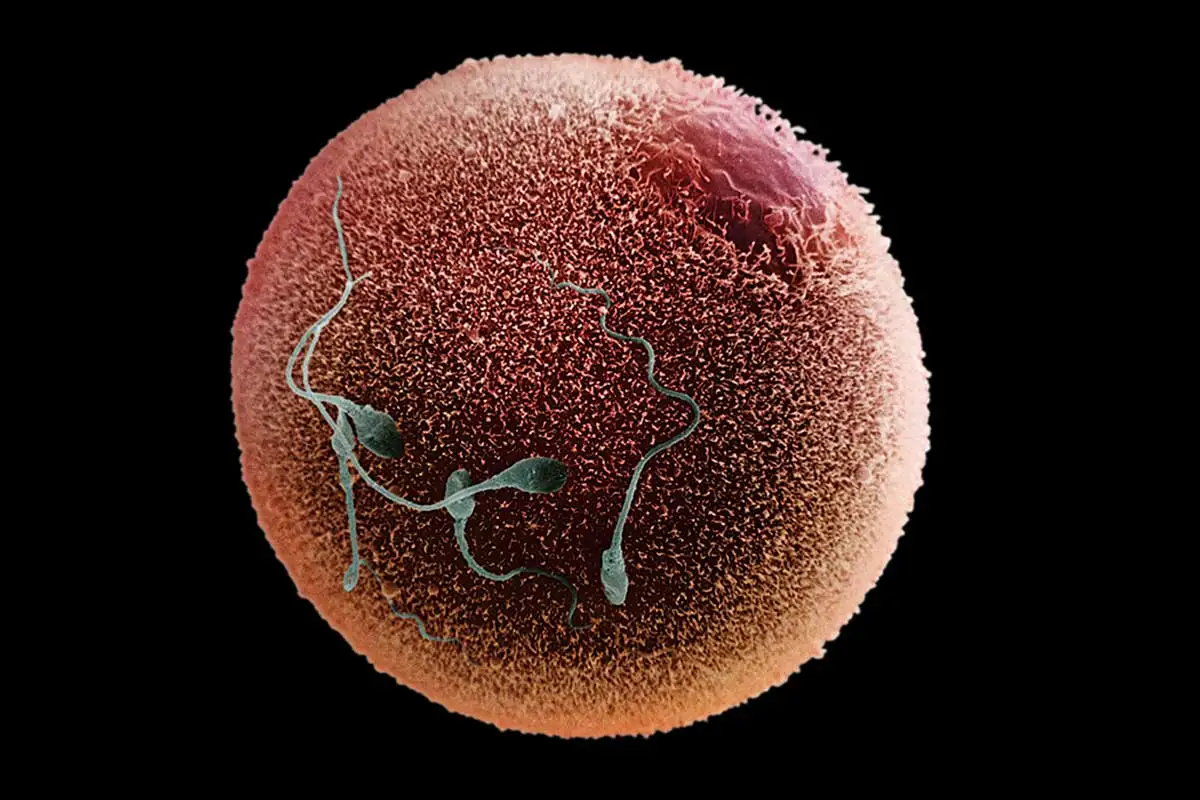

Scientists took the nucleus from a skin cell and placed it inside a donor egg whose own nucleus had been removed.

Because skin cells contain 46 chromosomes (instead of the 23 needed for eggs), they developed a new method called “mitomeiosis” to reduce the number.

They were able to create 82 eggs, fertilise them with sperm, and grow them in the lab.

After six days, about 9% of the embryos developed to a stage where, in theory, they could be transferred into a uterus via IVF.

Although some embryos showed abnormalities, experts say this is still a big step forward. In natural reproduction, only about a third of embryos reach this same stage.

Professor Ying Cheong from the University of Southampton called it an “exciting breakthrough,” saying it could change how we understand infertility, miscarriage, and future fertility treatments.

For now, though, the biggest challenge remains producing eggs that are genetically normal. Researchers also highlighted that the work followed strict U.S. ethical rules on embryo research.

In short: this is still early science, but it opens the door to a future where infertility might have new solutions — and even same-sex couples could one day have children who share DNA from both partners.