By Evans Ufeli Esq

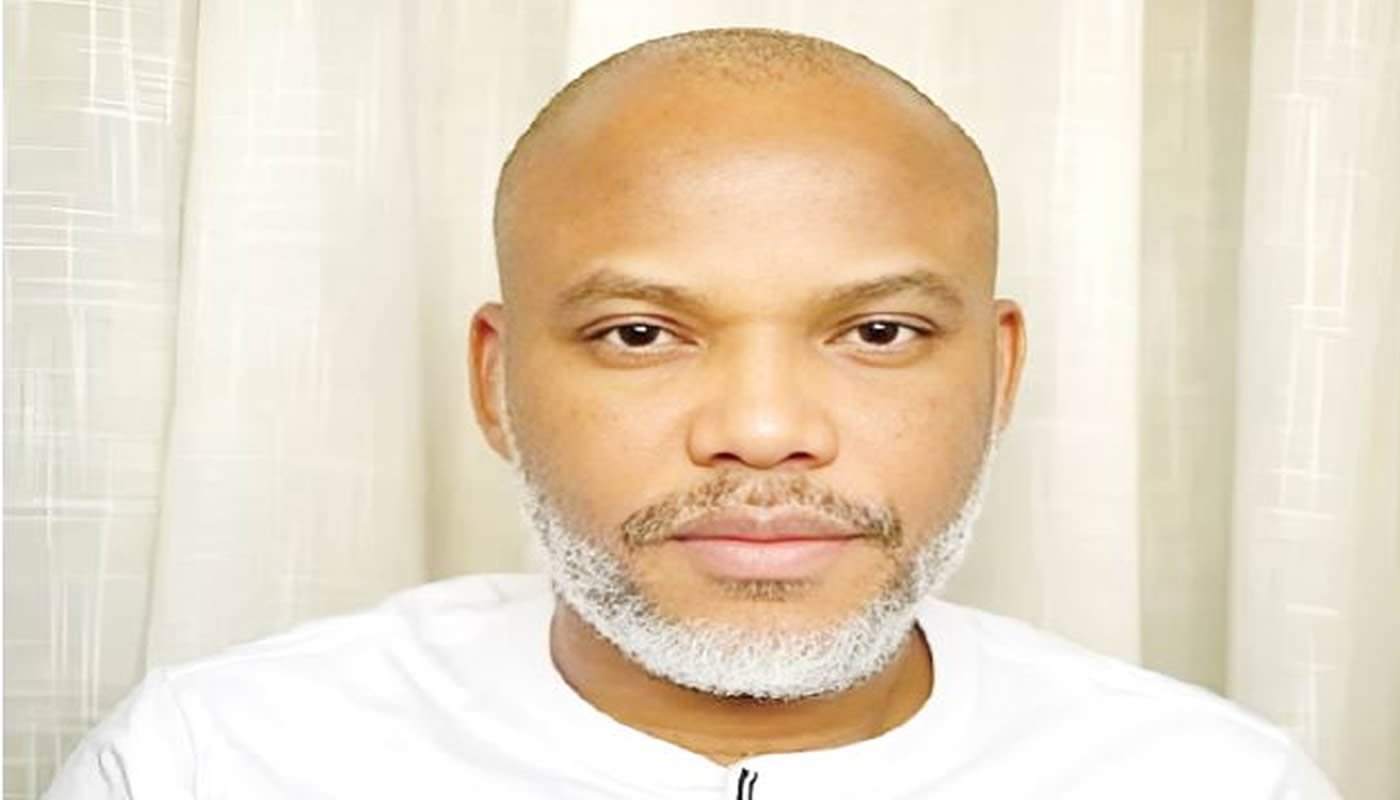

The judgment rendered against Nnamdi Kanu by Justice James Omotosho cannot be properly understood as merely the resolution of a criminal charge; it is also a test of basic legal architecture; the requirement that prosecutions be anchored to existing law, that proofs meet the criminal standard, and that courts respect the limits of their own jurisdiction.

Viewed against these bedrock principles, the conviction appears defective for at least three interlocking reasons: the statutory foundation for the charge was absent or invalid, the evidential record fell short of proving terrorism beyond reasonable doubt, and a fundamental objection to jurisdiction was not adjudicated before the merits. Taken together, these flaws raise the specter of a judgment formed ex nihilo; from nothing -contrary to both substantive and procedural law.

The first and most elemental objection is statutory. Criminal law proceeds on the maxim nullum crimen sine lege; no crime without law - and its corollary that a court may not convict on a basis that lacks a current legal foundation. The Latin adage ex nihilo nihil fit, “nothing comes from nothing,” captures this point with equal force: a conviction cannot validly derive from a legal vacuum.

If the Terrorism Act under which the accused was charged had been repealed prior to or at the time of prosecution, the court’s exercise of criminal jurisdiction in reliance upon that Act would have been without legal underpinning. The consequences are not merely technical. A law is the predicate that defines the prohibited conduct, prescribes requisite mens rea, and establishes the penalties. Absent that predicate, there is no correctly defined offence to try, no statutory elements to prove, and no lawful sanction to impose.

There are further legal nuances: the temporal relationship between repeal and the alleged offending conduct can matter, and the legislature’s intention regarding retrospective application will determine whether prior conduct remains punishable.

But those distinctions only reinforce the central point: the court must first determine whether the statute remained in force and applicable before it can proceed to adjudicate guilt under that statute. If a court ignores or misapprehends that statutory question, any conviction it pronounces risks being void for want of a legal foundation.

Separate from the statutory question is the quality and sufficiency of the evidence. Criminal trials are governed by the strict standard of proof beyond reasonable doubt precisely because the state wields its coercive power against liberty. This high threshold is not an abstract ritual; it demands that the prosecution produce evidence that establishes both the actus reus and the requisite mens rea for the charged offence to such a degree that a reasonable doubt about guilt is excluded. Where a prosecution alleges terrorism or related violent wrongdoing, the prosecution will ordinarily need to prove not only ideological intent or leadership of an organization but also concrete links to acts of violence or instruments used to effectuate violence.

In the case at hand, it is striking that no weapon was tendered in evidence linking the accused to violent acts, nor was there direct proof tying him to the commission of terrorist acts beyond reasonable doubt. The absence of a tendered weapon may seem, on its own, a narrow evidential point; but in the context of charges premised on violent conduct or the use of arms, it is material. Convictions that rely solely on circumstantial inference from speech, association, or political agitation require careful corroboration before the criminal standard is met. Circumstantial evidence is permissible, but it must form a coherent kernel that excludes other plausible innocent explanations. Uncorroborated assertions, hearsay, or reliance on the alleged dangerousness of speech without demonstrating an imminent or proximate nexus to violent acts will not suffice.

Moreover, the law distinguishes between mere advocacy or political dissent even if extreme or provocative and criminal responsibility for terrorism. The mens rea for terrorism typically demands proof of intention to cause widespread harm, coerce a population or government, or direct involvement in violent operations. Absent direct evidence of such intent or participation, and with the prosecution unable to produce key physical evidence linking the accused to violent acts, a conviction is vulnerable to attack as having been founded upon speculation rather than proof.

Perhaps the most significant procedural defect concerns the court’s refusal to hear an objection challenging jurisdiction. Jurisdictional questions go to the heart of a court’s authority to act; they are not peripheral technicalities. A valid challenge to jurisdiction; whether raising questions about subject-matter competence, territorial reach, or the applicability of a repealed statute places an obligation on the court to resolve those issues as a threshold matter. The reason is straightforward: if the court lacks jurisdiction, every subsequent step it takes is a nullity. Procedural fairness requires that jurisdictional obstacles be addressed before putting an accused to proof on the merits.

The failure to hear a preliminary objection is more than an error of procedure; it undermines the entire adjudicative sequence. Courts have long recognized that jurisdictional challenges are special in character and ought to be disposed of at the outset: a premature plunge into evidence and arguments on guilt risks expending both the parties’ rights and public resources on a process that may be void from the start. Where the objection raises a real question about the legal basis for the indictment, for example, whether the enabling statute was in force; the court’s duty to decide it is heightened. To proceed in defiance of such an objection is to invert the order of decision-making that the rule of law demands.

Taken together, these defects; an absent or repealed statutory basis, insufficient proof of violent conduct or connection to terrorism, and the court’s failure to entertain a jurisdictional challenge at the outset point to a judgment that is constitutionally and legally vulnerable. Remedies will depend on the court system and appellate processes available, but fundamental principles suggest that the conviction should be set aside or remitted for a new trial after the threshold jurisdictional and statutory issues are resolved. At a minimum, the matter warrants rigorous appellate scrutiny to determine whether the trial court exceeded its authority or resolved guilt without the legal underpinnings necessary for a valid conviction.

Read Also;

Kanu’s Family Rejects Court Ruling, Insists Constitution Was Violated

The importance of these principles extends beyond a single case. Democracies rely on courts to apply the law as written, protect the accused from arbitrary state power, and ensure that criminal sanctions are not imposed without proper statutory basis and proof. When courts allow convictions to be sustained where the statutory foundation is in doubt or the evidential threshold is not met, they erode the protections the criminal justice system exists to provide. To invoke ex nihilo nihil fit in this context is not mere rhetorical flourish; it is a demand for legal integrity. If nothingness; the absence of a law or valid jurisdiction is permitted to produce punishment, the system ceases to be lawful.

In summary, the judgment’s legitimacy depends on answers to three threshold questions: Was there a valid statutory basis for prosecution? Did the evidence prove the offence beyond reasonable doubt? And did the court properly determine its jurisdiction before deciding the merits? If the answers to any of these are negative, then the conviction cannot stand without contravening the core principles of criminal law and due process. Courts must be vigilant to ensure that no conviction is built on nothing.