By Evans Ufeli Esq

The unfolding litigation surrounding Fubara and the Rivers State House of Assembly presents a telling contest at the intersection of constitutional prescription and procedural exigency. At its core is an interlocutory ex parte order, directed against the Chief Judge of Rivers State, restraining the constitution of a seven-member panel to investigate alleged gross misconduct. Couched against the backdrop of section 272(3) and section 188(10) of the Constitution and existing authorities, the matter invites the court to balance competing constitutional imperatives; the autonomy of the legislature to discharge its investigatory and disciplinary functions and the duty of the courts to preserve individual rights and the rule of law.

An ex parte injunction, by its very nature, is provisional and anchored in urgent necessity. Its immediate effect is not illusory: a court’s command, even if temporary, carries the force of law and demands obedience until it is discharged or set aside by due process. In practical terms, the Chief Judge and the Rivers State House of Assembly must, as a matter of both principle and prudence, respect the subsistence of the order for the seven-day period specified. To do otherwise risks transgressing the boundaries of judicial authority and courting the very sanction that courts reserve for defiance of their processes; contempt. The salutary rule that “he who seeks equity must do equity” is mirrored here by the simpler maxim that courts’ orders bind until lawfully vacated.

Procedurally, the ex parte order sets the stage for more exacting contestation. The order subsists pending the determination of a motion on notice, the natural sequel to any provisional relief granted without full representation of the interested parties. Within that framework, the adverse parties will be entitled to file counter-affidavits and to advance preliminary objections, most notably on jurisdiction. Jurisdictional points are singularly grave in constitutional litigation; they are the gateway through which any substantive inquiry must pass. A challenge to the court’s competence to intervene will not only test procedural propriety but also engage constitutional architecture: whether the judiciary may, as a matter of principle and necessity, enjoin internal legislative processes designed to determine alleged malfeasance by a public officer under constitutional provisions such as section 272(3) and section 188(10).

The anticipated filings will crystallize the questions that the court must resolve. The House may argue, understandably, that the Constitution confers upon it an exclusive competence to initiate and prosecute impeachment or gross-misconduct proceedings, that the internal constitution of investigative panels lies within legislative domain, and that judicial intrusions risk upsetting the equilibrium of separation of powers. Conversely, the applicant will press the primacy of individual rights and due process safeguards, asserting that where a constitutional officer faces potentially ruinous internal proceedings, the judiciary is empowered to provide preservative relief if there is a real risk of irreparable harm or abuse. These are not novel propositions, but their application to the precise wording and intent of the cited constitutional sections will require careful adjudication.

The court’s task will be interpretative as much as adjudicative. The language of section 272(3) and section 188(10), and the precedents that have given them texture, must be read in the light of constitutional purpose: to ensure accountable governance without undermining the autonomy of constitutionally established organs. The judiciary must, therefore, navigate between two perils; the usurpation of legislative function under the guise of protection, and the abdication of its duty to guard against arbitrary or procedurally sterile exercise of legislative power. In doing so, the court will be called upon to delineate the contours of what constitutes a justiciable infringement upon procedural fairness and the point at which institutional prerogative immunizes legislative acts from judicial review.

Moreover, the forthcoming hearing on the motion on notice will allow the court to evaluate the adequacy of alternative remedies, the existence of any imminent or irreversible prejudice, and whether the statutory framework itself contemplates a self-contained mechanism that should be exhausted before judicial intervention. The filing of preliminary objections grounded on jurisdictional non-justiciability will press the court to articulate the limits of its supervisory jurisdiction and the circumstances in which it may grant interlocutory protection without impinging unduly upon legislative sovereignty.

Read Also;

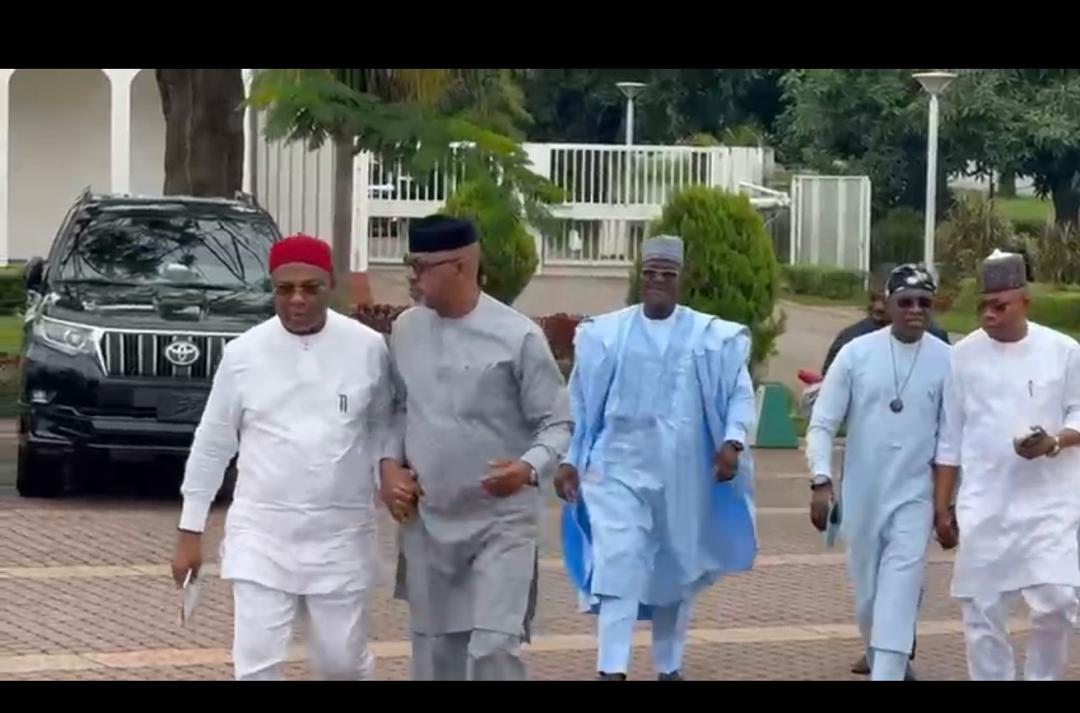

Rivers Lawmakers Reverse Course, Back Impeachment of Governor Fubara

It is also foreseeable that this litigation will contribute to the evolving jurisprudence on constitutional interplay between arms of government. Judicial pronouncements in the days to come may refine the interpretative lens through which sections 272(3) and 188(10) are applied, providing future guidance as to the availability of interlocutory relief where constitutional processes intersect with allegations of misconduct. The adjudication may, therefore, not merely resolve a single controversy but also furnish precedent that calibrates the balance between procedural autonomy and judicial guardianship.

In the immediate term, however, the operative position is clear: the ex parte order, once made, must be treated as binding for the period it was intended to subsist. Compliance by the Chief Judge and the House is both a legal obligation and a salutary act of institutional comity. Thereafter, the adversarial phase; the filing of counter-affidavits and preliminary objections, and the full hearing of the motion on notice; will provide the forum for a definitive judicial resolution. What emerges from that crucible will undoubtedly shape the contours of constitutional accountability in the State and, perhaps, contribute to the broader canon of constitutional interpretation in our jurisprudence.