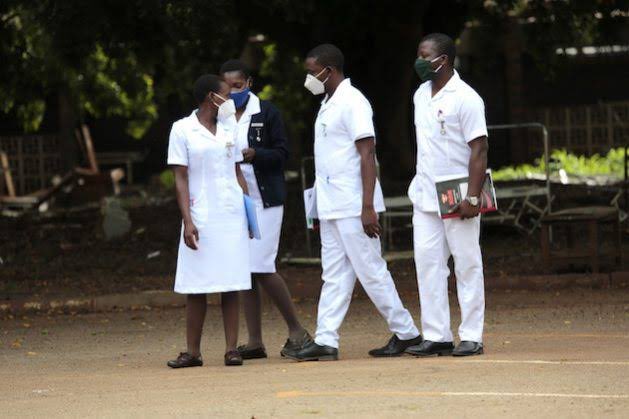

In the past five years, at least 14,815 Nigerian-trained nurses and midwives have migrated to the United Kingdom, driven by the search for better career prospects, according to data from the UK’s Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC). This significant outflow of healthcare professionals has sparked concerns about the growing strain on Nigeria's healthcare system.

Between April and September 2024 alone, 1,159 Nigerian-trained health workers were added to the NMC register, marking an 8.5% increase in just six months. As of September 30, 2024, Nigerians ranked third on the UK’s list of foreign-trained healthcare workers, behind India and the Philippines. Despite a 16.1% decrease in new additions compared to the previous year, Nigerian healthcare workers continue to make up a substantial part of the UK’s medical workforce.

While the NMC register indicates the number of healthcare professionals qualified to practice in the UK, it doesn't necessarily mean they are all employed. However, the steady increase in numbers since 2017 highlights a clear trend of migration among Nigerian nurses and midwives seeking better opportunities abroad.

The trend has raised alarms in Nigeria, with health authorities expressing concern about the growing brain drain and its impact on the country’s already strained healthcare system. Dr. Iziaq Salako, Nigeria’s Minister of State for Health, addressed the issue at the Association of Medical Councils of Africa (AMCOA) conference in Abuja, warning that the migration of skilled health professionals is putting significant pressure on the country's health sector.

“We train some of the world’s finest doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals, yet too often, they leave our shores in search of better opportunities,” Dr. Salako said. “While we celebrate their global impact, we must also confront the strain this places on our health systems and our economy.”

To address the situation, Dr. Salako called for stronger, legally binding agreements between African countries and nations like the UK to ensure that countries benefiting from the migration of health professionals contribute to the training and infrastructure needs of those nations. He also stressed the importance of creating better working conditions and incentives to retain healthcare workers in Nigeria.

Experts and healthcare professionals have repeatedly cited poor salaries, inadequate equipment, and harsh working conditions as major drivers behind the migration. Ifeoma Eze, a registered nurse in Lagos preparing to move to the UK, shared her frustration: “Nurses are overwhelmed and underpaid. Many of us work double shifts with very little support. It’s not that we want to leave home, but we want to grow and be valued.”

Unless decisive action is taken to address these challenges, Nigeria’s healthcare system may face even greater difficulties in the future, with an increasingly high number of health professionals choosing to seek opportunities abroad.